Strategic Approaches to Utility Facility Security

Adapted from a Q&A featured in Utility Security

In an era marked by persistent threats to critical infrastructure, securing utility facilities demands more than just cameras, fences, and policies—it requires a mindset shift.

Understanding vs. Installing

Clients in the utility sector focus heavily on installing high-profile assets like substations, perimeter fencing, and control centers. While these are critical to a successful security design, in many cases, it’s the unheralded risks that present the greatest threats. Insider threats, third-party vulnerabilities, or unprotected assets outside the direct control of the utility can create blind spots in an otherwise solid security program.

To manage these “known unknowns,” start with a comprehensive threat and vulnerability assessment (TVA). This assessment doesn’t just consider physical entry points, but also operational practices, interdependencies, and even the roles of third-party providers. For example, if a utility relies on a third party for natural gas supply, it must consider who is responsible for securing those shut-off valves. They also must consider if the handoffs are clearly defined and enforced. Understanding operational nuances like these is critical for building a truly resilient program.

Balancing Form and Function Through Design

Utility infrastructure often sits at the intersection of functionality and community visibility. While some may argue that security must be overt and robust, it can also be seamless and smart. That’s where integrated design plays a powerful role.

Using Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) principles, security professionals can incorporate natural surveillance, strategic landscaping, lighting, and layout choices that deter crime without creating the appearance of a fortress. A facility can remain welcoming to visitors and efficient for employees while being well-protected against threats.

Security should never be a bolt-on feature. When engaged early in the design process, security design professionals can influence everything from the selection of a building site to the layout of access routes, setbacks, and entry points. This mitigates risk before a single piece of technology is deployed.

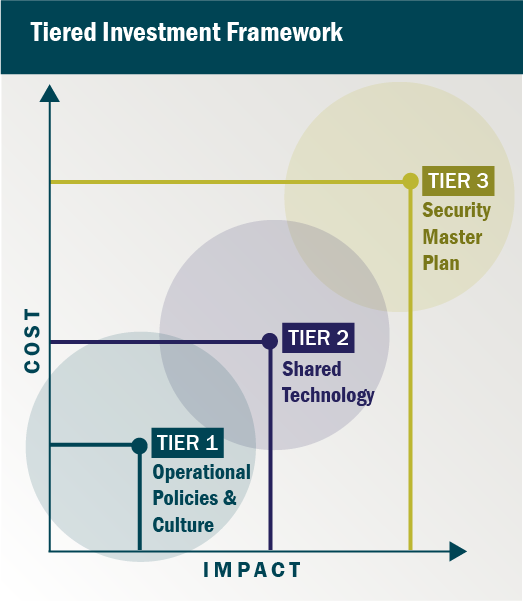

Smart Investment Through Multi-Tiered Planning

Not every utility has the budget for a full-scale overhaul, and they shouldn’t need one to begin making meaningful improvements. It’s best to deploy a tiered approach:

Tier One: Focus on operational and cultural improvements like clear policies, basic CPTED improvements, and building a culture of security awareness. These highly-impactful efforts come at a low cost.

Tier Two: Look into shared investment. Many security technologies can provide value to multiple departments. A thermal camera, for instance, enhances both security monitoring and maintenance diagnostics.

Tier Three: Develop a Security Master Plan (SMP) rooted in a TVA. An SMP aligns all stakeholders around shared priorities, provides traceability for risk, and ensures that security improvements are strategic and not reactionary.

By following this framework, utility organizations can move from ad hoc spending to a long-term investment strategy rooted in risk mitigation and operational integration.

Collaboration Is the Real Force Multiplier

One of the most overlooked factors in effective security is collaboration. Security teams must earn a seat at the table early in the planning process—whether it’s new construction, upgrades, or process changes. When security is involved from the outset, we can identify dual-purpose solutions, reduce redundant costs, and future-proof investments.

Building a culture of shared responsibility is very important. In utilities, safety is often a universal value, woven into everyday practices. Security should be treated the same way. When employees are trained, engaged, and empowered to report concerns, they become an extension of the security team and an invaluable force multiplier.

Learning Across Industries

Some of the most innovative security strategies come from outside the utility sector. Airports, for instance, are leaders in access control analytics. They monitor employee access patterns and detect anomalies—like an employee using an unfamiliar door—as potential early indicators of insider threat. Educational institutions, meanwhile, have mastered the deployment of mass notification systems that deliver real-time alerts across multiple platforms.

Utilities can and should borrow from these playbooks. Integrated video analytics, intelligent access control, and cross-functional communication systems are increasingly affordable and adaptable.

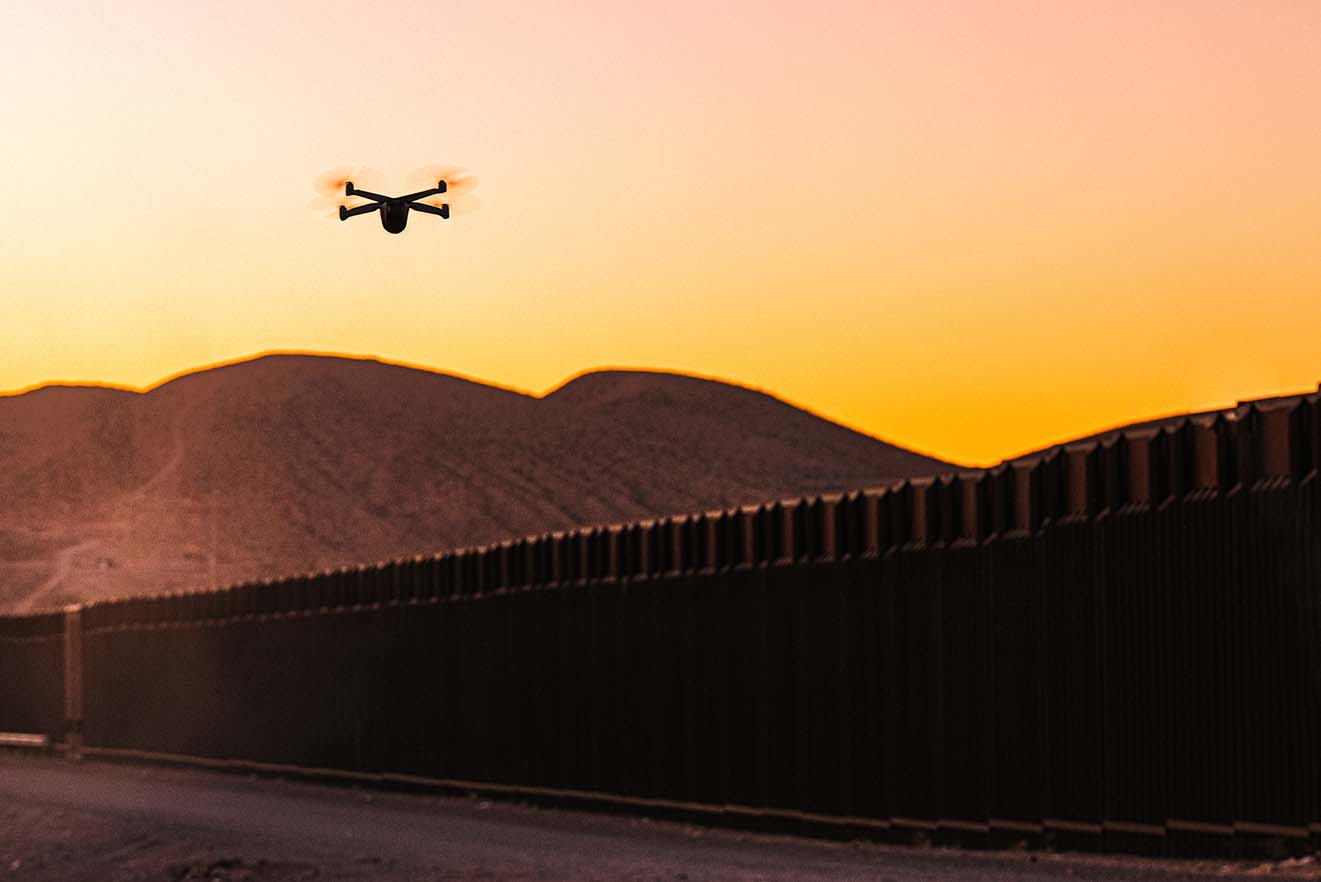

Looking Ahead: Drones and Activity Intelligence

As we look to the future, two threats concern me most: drones and homegrown violent extremists (HVEs).

Drones are increasingly accessible and capable of carrying dangerous payloads. While they are invaluable for legitimate inspection and monitoring, their misuse poses a real threat to unprotected utility infrastructure. Utilities must begin exploring drone detection and response technologies now before drone misuse becomes a widespread problem in the United States.

HVEs, on the other hand, represent a more insidious challenge. These actors may already have access or operational knowledge of a facility. Combating this requires activity intelligence—security systems that learn normal behaviors and flag anomalies. This isn’t just about identifying access to the wrong door; it’s about recognizing when someone deviates from their baseline behavior.

The Future Is Proactive, Not Reactive

Security is no longer about gates and guards—it’s about data, design, and dialogue. A utility’s ability to protect its infrastructure depends on early planning, cross-departmental collaboration, and an informed, engaged workforce.

As security risks become more sophisticated, we must move beyond a checkbox mentality. By embracing integrated, scalable, and intelligence-driven strategies, utilities can not only mitigate today’s threats but also prepare for those just over the horizon.