Municipal Climate Laws Accelerate Shift to Fully Electric Buildings

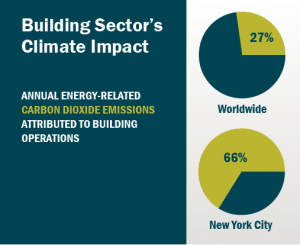

Across the country, ambitious municipal climate change laws are going into effect.

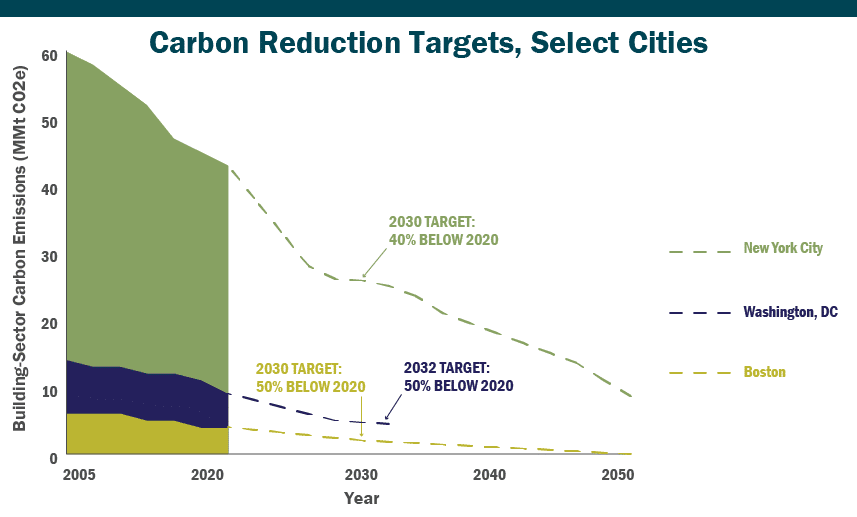

Nearly half of major U.S. cities have committed to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, aligning with global targets to significantly cut emissions by 2050.

Initial efforts focused on the carbon footprint of government-owned buildings or set minimum standards for newly constructed buildings. Recent policies now require existing, privately owned commercial, institutional and multifamily buildings take action as well. Non-compliance will result in significant fines.

As property owners confront their emission-reduction obligations, it will be important to prepare well in advance of compliance deadlines. Lowering the carbon intensity of their buildings will likely involve major infrastructure modifications and potentially require adding new sources of reliable power.

From Energy Benchmarking to Building Performance Standards

Across the country, more than three dozen municipal benchmarking ordinances mandate large property owners disclose annual energy consumption. This level of insight allows facility managers, renters, buyers and financiers to compare energy-efficiency performance between buildings, potentially motivating owners to undertake voluntary retrofits.

Benchmarking policies have provided the basis for more-aggressive measures. In the last three years, a wave of state, county and city laws have established emission caps that will become more stringent over time.

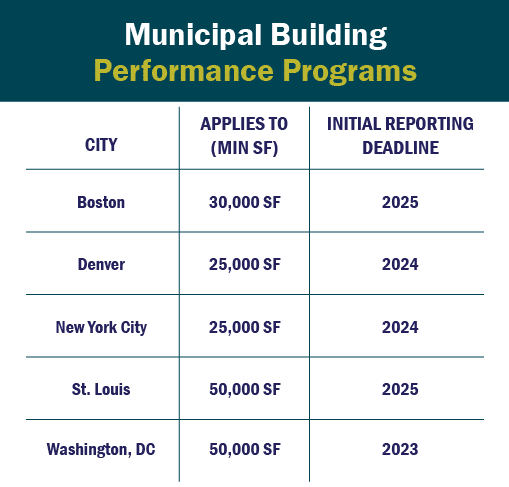

Municipalities with building emission-reduction or energy-performance standards include:

- New York City’s Local Law 97

- Boston’s Building Emissions Reduction and Disclosure Ordinance

- Washington, D.C.’s Building Energy Performance Standards (BEPS) Program

Other policies include state-wide programs still under development in New York, Maryland and Washington as well as ordinances passed by cities such as Denver and St. Louis.

Each program will be structured differently. In general, owners can comply by verifying either:

- Carbon emissions per-square-foot (emission intensity) within a threshold set for their specific building category

- An energy-efficiency score at or beyond the level established by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s EnergyStar Portfolio Manager system

- A customized emission-reduction action plan

New York City Local Law 97

Passage of New York City’s groundbreaking 2019 Climate Mobilization Act imposed one of the building sector’s most-aggressive carbon limits as well as among the highest non-compliance penalties.

Most buildings larger than 25,000 square feet will be required to report emission-intensity scores. Stricter limits are scheduled to go into effect in 2030, helping the city reduce emissions from the largest buildings 40 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050.

Emission intensity is based on the carbon dioxide equivalent of all electricity, gas, steam, and other fossil fuels consumed on site.

While Local Law 97 encourages energy efficiency retrofits or on-site renewable energy installations, the program also offers some level of flexibility. Owners can purchase carbon offsets or enter into power purchase agreements to satisfy a portion of their emission reductions.

Buildings that fail to achieve their required reduction must pay annual penalties. Fines are based on the building’s carbon dioxide emissions, measured per square foot, in excess of the property’s carbon limit.

Program architects say it was designed to achieve environmental progress, not to collect fines. Former City Councilmember Costa Constantinides, who chaired the Committee on Environmental Protection during passage of Local Law 97, once said: “I don’t want anyone’s money. I want your carbon.”

Reducing Emissions in Aging Buildings

Compliance will pose challenges for buildings of all sizes and classes. Decarbonizing older buildings may prove to be especially difficult.

The most-effective pathway involves heating and cooling systems. Replacing legacy steam, gas, or fuel oil systems with electric alternatives will reduce emissions — but at a cost. In most buildings, major modifications are necessary to modernize aging mechanical and electrical systems.

Electric heat pumps offer a practical solution, especially for buildings reliant on high-temperature hot water systems. Additional heat options include heat-recovery ventilators (HRV) and energy-recovery ventilators (ERV) that recirculate pre-warmed air normally wasted as exhaust.

Reliance on electric distribution systems will necessitate additional back-up power supplies and resilient heating sources. Building owners who upgrade to heat pumps may want to consider an on-site hybrid heating system that can use natural gas or a redundant power supply in the event of power outages or price spikes.

To better track and forecast future emissions, sophisticated energy management systems can help facility teams monitor consumption trends and more accurately predict their performance.

With heating systems generally representing a facility’s largest energy loads, the building’s electrical infrastructure will need to be assessed prior to electrification. In buildings with limited electrical capacity, owners may need to work with their utility company to upgrade or add electrical service.

Compliance Requires Advanced Planning, Expertise, Money

Achieving ambitious emission-reductions plans will likely involve a significant investment of time and resources.

Property owners should coordinate with an engineering partner well ahead of local compliance deadlines to ensure their buildings can satisfy performance targets.

For owners considering whether to simply pay a non-compliance fine, programs such as New York City’s Local Law 97 were designed to structure fees that mirror the estimated cost of an average building retrofit. That said, costs for labor and equipment vary considerably — with inflation causing prices to rise significantly since the law was enacted.

State and utility incentives can help recover some upfront costs. Generous rebates can reduce costs for high-efficiency heating, ventilation and air conditioning upgrades. In some states, however, utilities are restricted from offering incentives that encourage ratepayer “fuel switching” and reduce the competitiveness of certain energy suppliers.

Burns Engineering can assist building owners evaluate compliance pathways, leverage available funding, and determine the most cost-effective solutions. Proactive owners can meet their obligations while ensuring their buildings remain financially and environmentally sustainable for years to come.

Featured photo by Udayaditya Barua on Unsplash